DGI vs. Indexing: No clear winners in this fight.

Saving regularly and having a zero or manage-ably low debt are important prerequisites for efficient long-term investing. You can’t think of investing until your savings is building up. If you are a diligent saver or have sizable funds already, this series of articles is for you because it is about investing those savings. After you are convinced that a stock-heavy investment portfolio is efficient, then you have to answer another important question of which investment method works best for you – passive indexing, and somewhat active but self-directed dividend investing? It’s like the ultimate standoff – Coke vs. Pepsi. And like the cola wars, there is no single clear winner. Both are good and can get you to your destination (FIRE). But the ‘winner’ depends on you – the investor.

Active Fund vs. Index Battle is Over

The holy grail of passive investing is based on the premise that most active fund managers cannot beat the returns of their benchmark index, after fees and taxes. The key difference is fees. If you can invest in an index fund (like VTSAX or its ETF-equivalent VTI) at an ultra-low 0.05% fees, an average active equity fund charging 0.7% fees has to beat the index performance by 0.65% every year, just to break-even with what the index fund can deliver. A 0.65% performance difference may not sound big, but consider this: In an environment where future returns are only about 6%, this 0.65% is more than 10% of the index’s average annual return. When every analyst in every financial institution in the world is looking for that ever-so-elusive trading advantage, one fund company beating the index by more than 10% every year is a huge ask. If they miss by even one year, the index will surpass them.

As if this barrier is not enough, active fund managers also have to deal with ‘cash drag’ – they are forced to hold a significant percentage of the fund assets in cash to cover redemption’s from investors. If a fund holds 5% in cash yielding 0%, then the remaining 95% invested have to generate 5.26% more return (100/95) to match 100% equity index return. In addition, because they are ‘active’, they trade stocks frequently in the hope of capital gain so, they incur brokerage fees and short term capital gain taxes – both of which are ultimately borne by fund investors. Even their costs to get the word out about the fund (marketing costs and ’12b-1′ fees) are charged to investors – all of which reduce the final return realized by investors, net of all taxes and fund expenses.

So, it’s a no-brainer why an index fund beats more than 80% of all active management funds. The sheer simplicity of it with the excellent results an average investor can realize makes indexing an attractive investing choice. All studies on safe withdrawal rates (SWR) are based on broad market indexes, so if you are an index investor, the SWR studies (whether you withdraw 3%, 3.5% or 4% or even 5%) can directly apply to your retirement portfolio.

So, is indexing the obvious winner? Well, not always.

The comparison in this article is not between index funds and active funds – that battle was handily won by index funds. A savvy investor has another way to look at equity investments. If you consider that retirement investing is ultimately about creating inflation-adjusted passive income, a different method can be pursued. Equity investors with interest to do basic research and monitor their portfolio can use dividend growth investing (DGI) as their strategy. Actually, both indexers and DGIers are part of the same class of equity investors – the only difference is in their approach. There are enough articles on DGI and indexing that I am not getting into portfolio construction and related minutiae. Here at Ten Factorial Rocks, we will use a different lens to analyze DGI vs. Indexing debate.

DGI vs. Index Battle Will Remain

Both camps passionately believe in their approach and trounce the weaknesses of the other camp. But TFR believes the fight is about splitting hairs. Asset allocation determines the lion’s share of the return, so whether indexing or DGI, if both are 100% equities with similar split between U.S. and international holdings, then the returns cannot be very far apart. Both approaches have merit and the selection of indexing or DGI or even both depends on the temperament and interests of the investor. A diehard indexer would point out stock selection risk (causing index lag) and the potential for dividends to get cut as weakness of a DGI strategy. A hardcore DGIer would talk about living off dividends alone without touching the principal, so that the underlying portfolio value – which is at the mercy of the fickle Mr. Market – worries indexers and not them. Importantly, a DGIer will emphasize not needing to sell equities at the wrong time (like in a deep bear market) just to generate spendable income.

Each camp overstates the limitations of the other camp in my view.

Income (from dividends) is stable, capital gains are fickle.

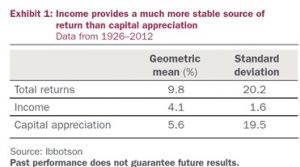

Dividends are an important part of the compounded total return, which both camps agree. While dividends can get cut in recessions, they are generally stable. The Ibbotson study shows the high predictability of dividends over capital appreciation. The data over a 87-year period summarized in the table clearly shows that dividends are far more stable (just 1.6% std deviation) than capital appreciation (19.5% std deviation). So, an investor can count on his/her dividend getting paid quarterly (or monthly in some cases) much more than what the price of that dividend-generating stock will be.

Why are a company’s dividends so stable? Simple – the Board wants it that way. For a company’s board of directors, the dividend is an important policy matter and a key driver of shareholder value return. “If you don’t increase, at least don’t cut it” is the motto most boards live by. Also, longer the track record of paying dividends, more a company wants to maintain its record. It becomes a matter of pride and tradition at that point.

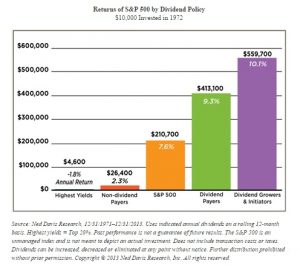

While share price growth is not what many DGIers pursue, study by Ned Davis Research shows that companies that pay dividends and/or grow them tend to perform better than the S&P 500 index, perhaps because they allocate capital more efficiently (if a company is ‘forced’ to payout 60% of earnings every year to shareholders as dividends, then only the best projects can afford get funded with the remaining 40%, thereby increasing future earnings).

While share price growth is not what many DGIers pursue, study by Ned Davis Research shows that companies that pay dividends and/or grow them tend to perform better than the S&P 500 index, perhaps because they allocate capital more efficiently (if a company is ‘forced’ to payout 60% of earnings every year to shareholders as dividends, then only the best projects can afford get funded with the remaining 40%, thereby increasing future earnings).

Companies hate to cut dividends even during recessions and some even continue to increase them (examples: consumer staples companies and McDonald’s in 2008-09). In the Great Recession of 2008-09, the dividend-paying companies in S&P 500 cut their dividends, in aggregate, only by 25%. Remember, that’s a worse case scenario as the financial and mortgage markets blew up, credit completely froze and every dollar was valuable to a company for bare survival. For a period worse than 2008-09 for dividends, you have to go all the way back to Great Depression in 1930’s when 70% dividends were eliminated and it took nearly a decade then to restore them fully. So, a right way to think about dividend risk is to consider a 25% cut during deep recession.

To a DGIer, having a diversified portfolio of 20-30 (for some, 100+) dividend paying stocks representing at least 8-10 industries of the economy (each with a good dividend track record) allows an investor to handle a recession with very little impact. Once you hold nearly 30 large companies diversified across industries, your returns start to mimic the S&P500 index because most of the index’s returns come from the top 1-2 companies in each sector.

The fee issue is largely irrelevant for both strategies, as both cost very little for a reasonable portfolio size. If you trade very little (as you should), building and maintaining a DGI portfolio of 20-30 stocks worth $250K would actually be cheaper than the expenses of a similar value invested in index fund (see example here).

Bear Market? Both Strategies Adapt.

You can avoid selling stocks at the bottom of a bear market with both strategies. Dividends, while very stable, are only a company’s Board policy and not an investor’s birthright. Even if dividend cut happens in a well-diversified portfolio (say 25%, as in the Great Recession), one can manage without selling stocks if the early retiree has been saving some cushion from prior year dividends (say, 5%). This comes in handy during the deep dividend cuts (which are very rare, as we saw above). Five years of 5% savings of your portfolio’s dividends can compensate for a 25% cut in one recessionary year. So, a DGIer can easily live with the dividend cuts till the economy improves and until the dividends are restored (like they were in 2010-11) and resume their growth path again.

Similarly, even indexers don’t have to sell at the wrong times if they keep a cash cushion. Remember, even the index pays dividends (S&P 500’s current dividend yield is about 2%), so the cash cushion for one year is sufficient for most index investors. DGIers don’t need any cash cushion beyond what they save from their dividends after living off them. A DGIer doesn’t have the cash drag that the indexer will have – that is, the drag of holding say, 8% cash, if the indexer decides to keep 2 years worth of living expenses in cash. Both methods offer enough flexibility for an investor to manage during tough times.

Nothing magical about dividends.

One important point gets blurred in this debate between Indexing and DGI. That is, the safe withdrawal rate (SWR) afforded by both strategies cannot be vastly different. Dividends are not ‘magic beans‘ and they are certainly not ‘free’ money as some wrongly assume – they are nothing but a share of the previous quarter’s or year’s profits that the company has chosen to share with stockholders. After paying dividends, that money is no longer available to the company to invest for other purposes. Just like there are indexes of many types, so are dividend-paying stocks. Some pay less than 1% yield, some pay 3-5%, and yet others pay substantially more, like 8-12%. Similarly, annual dividend growth rate (DGR) also varies widely across companies, from some at 0% (no dividend growth) to some at 20+% per year (very high growth) and everything in-between. Living only on dividends, especially since the dividend yields vary so widely, doesn’t mean you can ignore the research-based SWR thinking that considers both ‘sequence of returns’ risk and bear market draw downs. More on this in a future article.

DGI or Index? Think Differently.

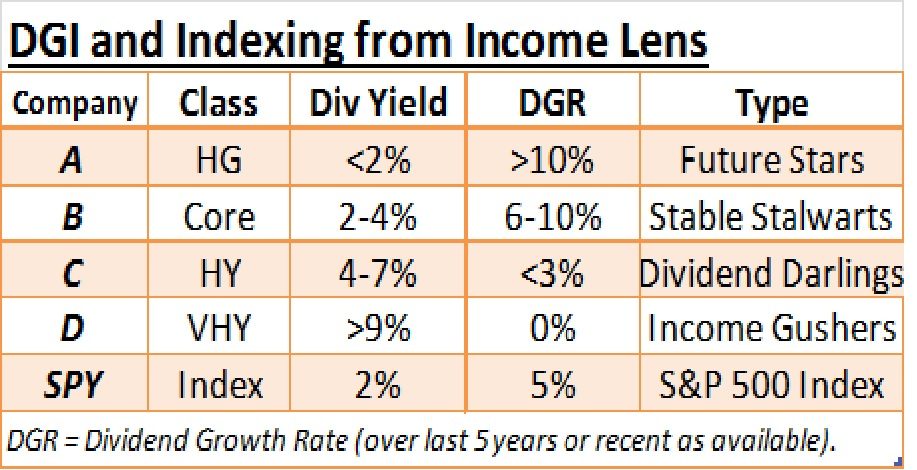

The table below lists 4 types of companies, and their dividend yield (along with S&P 500 index). Like the various investors seeking passive income, the assets that generate this income are also varied, each appealing to a different type of income-seeking investor. The value of a DGI approach (to a self-directed investor who is willing to put in the effort) is that the investor can ‘assemble’ a portfolio of investments of each company type below to arrive at the desired dividend income. You can almost tailor-make your investment portfolio (within reason) to meet your income goals. As a general rule, which the table below shows as well, higher a company’s current dividend yield, lower its annual dividend growth. This makes sense, right? There is no free ‘passive’ lunch (you can’t have both high current income and high growth – market mis-pricing can happen but not often, as high growth companies also have high P/E ratios making their current dividend yields relatively lower).

We will talk about each of these companies (with investor examples) versus the Index in subsequent posts.

Raman Venkatesh is the founder of Ten Factorial Rocks. Raman is a ‘Gen X’ corporate executive in his mid 40’s. In addition to having a Ph.D. in engineering, he has worked in almost all continents of the world. Ten Factorial Rocks (TFR) was created to chronicle his journey towards retirement while sharing his views on the absurdities and pitfalls along the way. The name was taken from the mathematical function 10! (ten factorial) which is equal to 10 x 9 x 8 x 7 x 6 x 5 x 4 x 3 x 2 x 1 = 3,628,800.

15 comments on “Dividend Investing vs. Indexing – Part 1”